Contributed by: Joshua C., FreeTaxUSA Agent, Tax Pro

If you sold your home during the year, it’s important to calculate the adjusted basis accurately when reporting the sale on your tax return. This figure determines how much gain (or loss) you realized when you sold the property — and that in turn determines whether any of the gain is taxable after the home‑sale exclusion (if applicable).

Here we’ll explain what adjusted basis is, how to calculate it, common special situations, how it affects your tax reporting, and what forms and records you’ll need.

What is adjusted basis and why does it matter?

- Adjusted basis is your investment in the property for tax purposes. The amount includes your original basis (purchase price), certain acquisition costs, capital additions (major improvements to the home), and possible reductions, such as special assessments or depreciation.

- The gain or loss you realized on the sale of your home is the sale price subtracted by your adjusted basis.

- In most cases, an exclusion is available (up to $250,000 for single filers or $500,000 if married filing jointly) if the home was your primary residence.

- If the property was used for rental or business purposes and qualified for depreciation (including a home office), you must reduce basis by the depreciation allowed or allowable. That portion of gain is not excludable and may be subject to depreciation recapture.

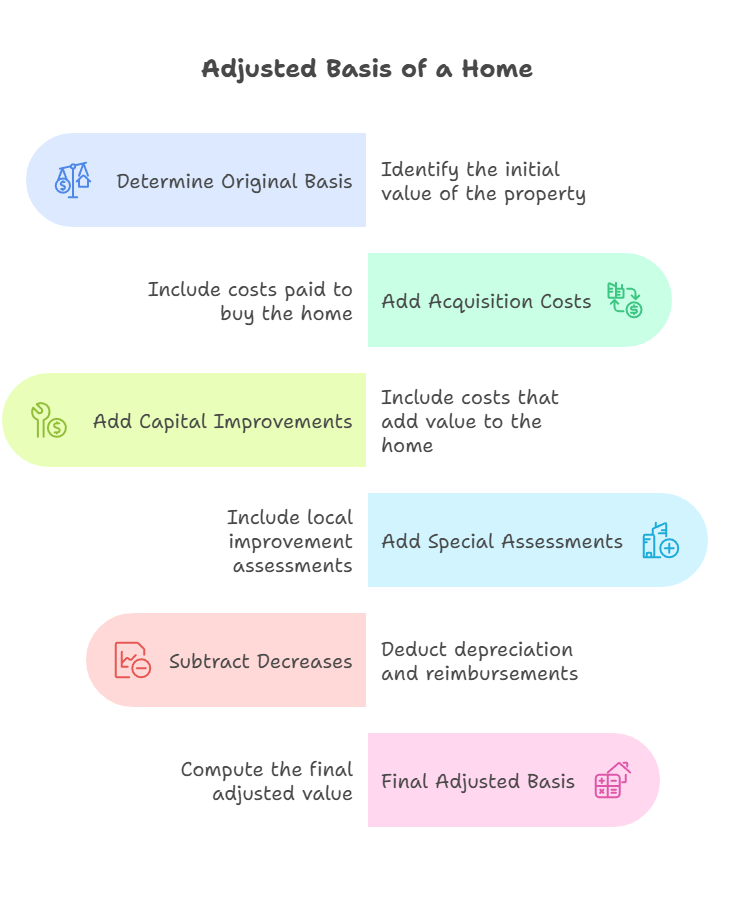

Step‑by‑step: how to calculate adjusted basis

- Determine the original basis

- If you purchased the home, your original basis is the purchase price (what you paid).

- If you inherited the home, your original basis is generally the fair market value at the decedent’s date of death.

- If you were gifted the home, your original basis is generally the donor’s basis, with special rules if gift tax was paid.

- For more detailed information about basis, including special rules, see IRS Publication 551.

- Add acquisition costs that increase basis. These are costs you paid to buy the home that aren’t deductible, such as:

- Title insurance, deed recording fees, transfer taxes

- Survey costs and certain legal fees for the purchase

- Settlement/closing costs, not including those related to financing (such as seller-paid points), and current property taxes included in the seller costs

- If you built your home, include the cost of land plus the amount it cost you to complete the house.

- Add capital improvements. These are costs that add value, prolong the home’s useful life, or adapt it to new uses, such as:

- Additions, new roof, new HVAC, kitchen remodel, new septic, finished basement, major landscaping, or a new driveway

- Do NOT include ordinary repairs and maintenance costs in the basis (painting, small fixes, cleaning, minor repairs).

- Add special assessments

- Local improvement assessments that increase property value are added to basis (e.g., for sidewalks, sewers). These are relatively uncommon.

- Subtract decreases to basis

- Depreciation allowed or allowable for any part of the property used for rental or business activity (including home office depreciation). The IRS requires basis to be reduced by all depreciation allowed or allowable even if you didn’t claim it.

- Insurance or other reimbursements for casualty loss.

- Final adjusted basis: Adjusted basis = original basis + acquisition costs + capital improvements + qualifying assessments − decreases (depreciation, reimbursements).

For more detailed rules and examples about basis adjustments on a home sale, see IRS Publication 523.

Example

Jasmine purchased her home for $300,000 and paid closing costs totaling $5,000. While she owned the home she remodeled and updated her kitchen and replaced the roof, which together totaled $40,000. She also rented out a room for a few years, during which she was able to claim $7,000 in depreciation on her tax returns. Her adjusted basis is calculated as follows:

- Original basis + closing costs + capital improvements – depreciation = adjusted basis

- $300,000 + $5,000 + $40,000 - $7,000 = $338,000.

Tips and considerations

Remember to keep records to support the numbers used in your calculation. Retain closing documents, receipts, invoices, permits related to improvements, records of depreciation, etc.

If part of the property was used for rental or business activities, pay close attention to depreciation recapture rules. These can be tricky and have a significant impact on your tax result.

Finally, up to $250,000 of the gain ($500,000 if married filing jointly) from the sale of your main home can be excluded from your taxable income as long as you meet ownership and usage tests.

It’s important to use the correct adjusted basis for the calculation to ensure your tax return is filed accurately. As long as you follow the steps outlined above and keep good records, you can calculate this figure without too much trouble.